Why Are We Still Writing CRUD UI With Hands?

Claude can write perfect UIs and Backends, but why is it writing React at all?

Markdown for AI Agents

Markdown for AI Agents

Code is an implementation detail

For internal tools and business apps, the UI requirements are predictable: forms, tables, dropdowns, modals, filters, pagination. Maybe some charts. Maybe a wizard with multiple steps. This class of application (the admin panel, the CRM dashboard, the inventory manager) represents a massive chunk of software.

AI generates this code effortlessly. The patterns are well-documented, the components are standardized, and AI has seen millions of examples. But the output is still code: hundreds of lines of React with hooks, effects, imports, state management.

That code is an implementation detail. It's one possible rendering of what the application is. And once you have code, you inherit all of code's problems: it needs maintenance, it's tied to a specific framework, it drifts from the spec, it breaks when dependencies update.

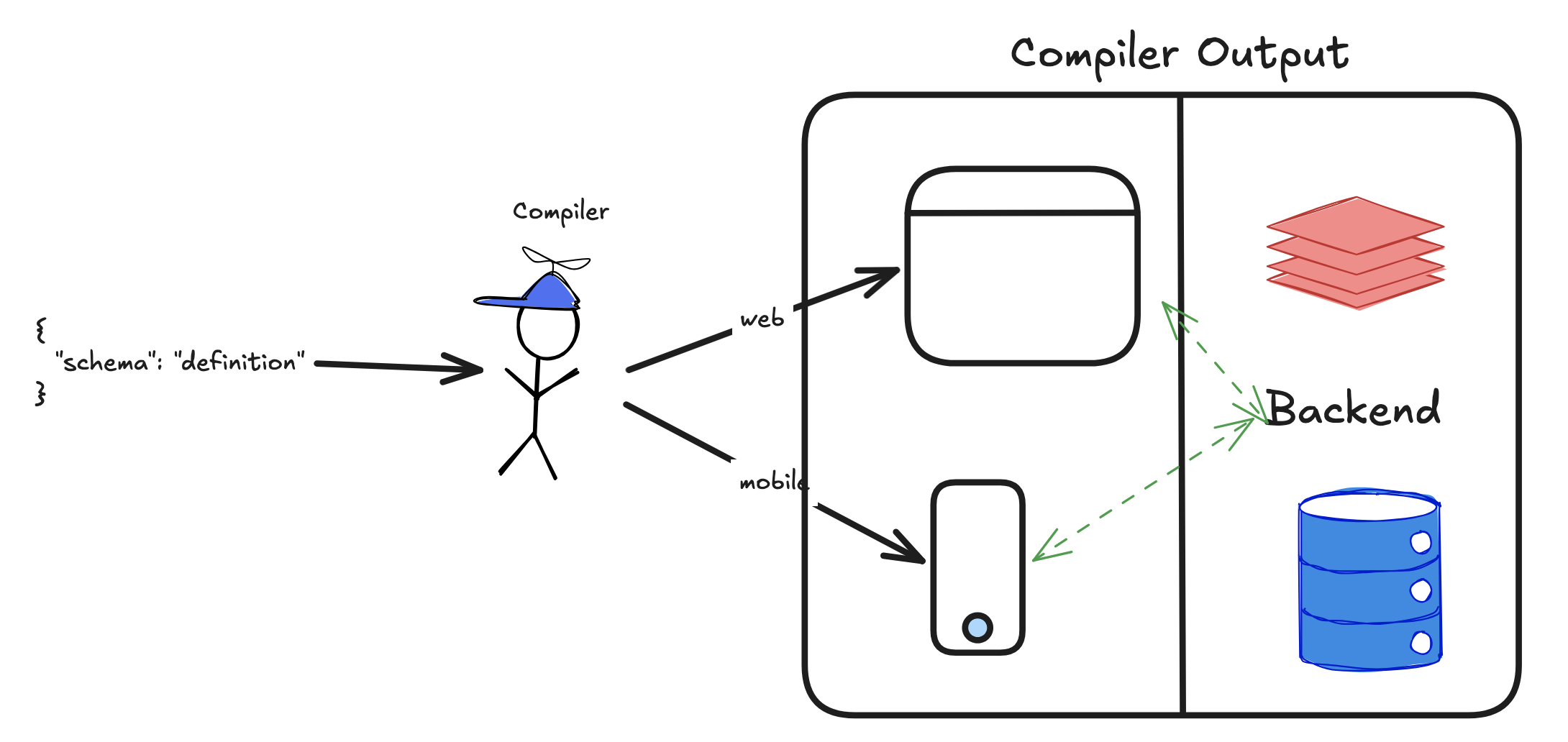

What if AI produced the specification and something else compiled the spec into working code ?

I was rambling about this idea four years ago in a conversation with Anand Chowdhary. Back then, I couldn't build it alone. The runtime is complex, the ecosystem integration is harder, and without AI to generate the schemas, who would write them by hand?

What I missed back then: the UI isn't the whole picture. UI is a DAG, and the leaves of that DAG trigger actions. When you fill out a signup form, you get added to the database and receive a validation email. The entire flow, from input fields to backend mutations to side effects, needs to be part of the schema. Not just what the user sees, but what happens when they act.

Now the pieces are falling into place.

Two approaches that miss the mark

People have tried to solve this before. The solutions fall into two camps.

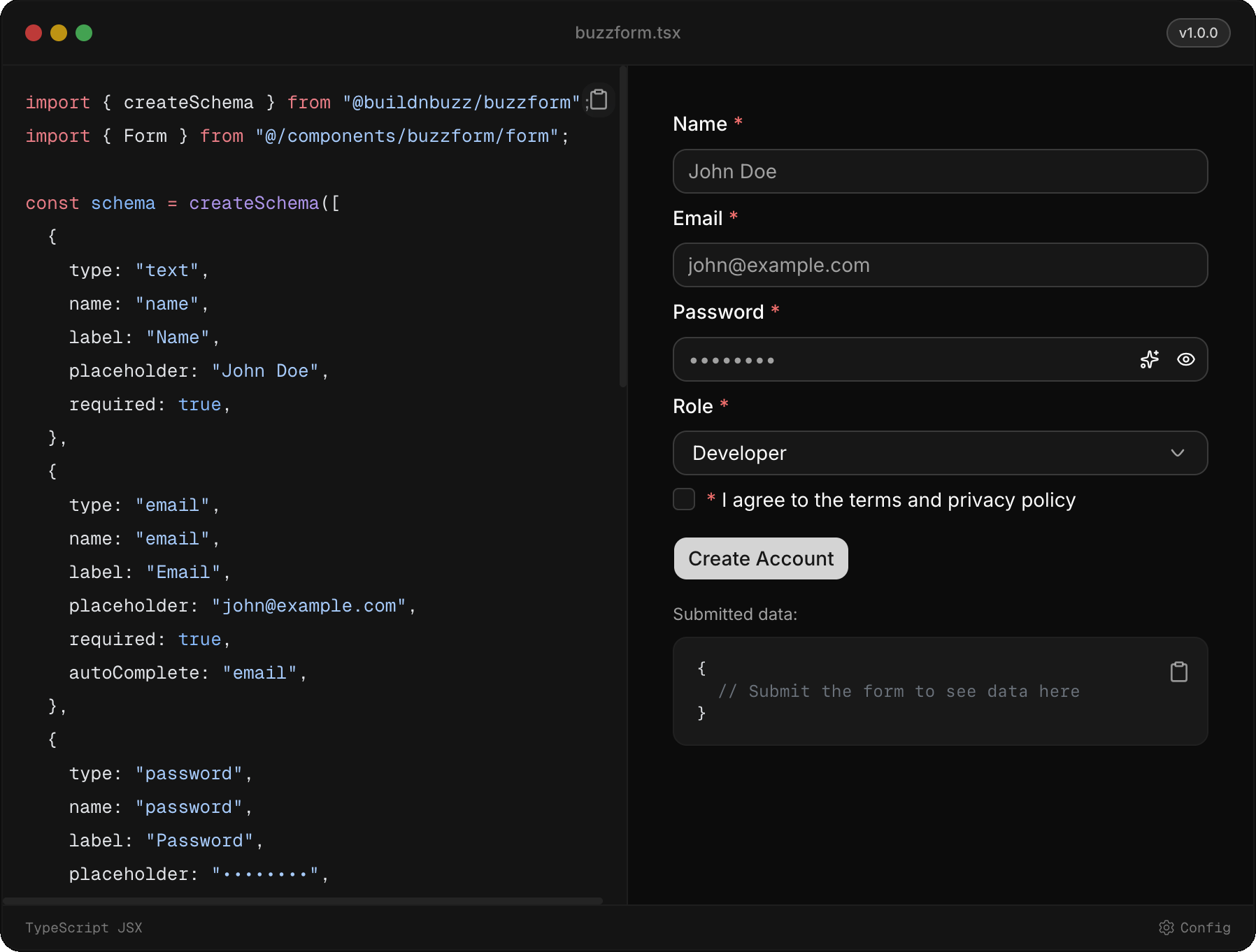

Schema-to-form generation

Libraries like JSON Forms and Buzz Forms take a data schema and generate UI. Define your fields, get a form. The approach is appealing: your database schema becomes the source of truth.

But UI holds runtime information. It carries more than a data schema ever could.

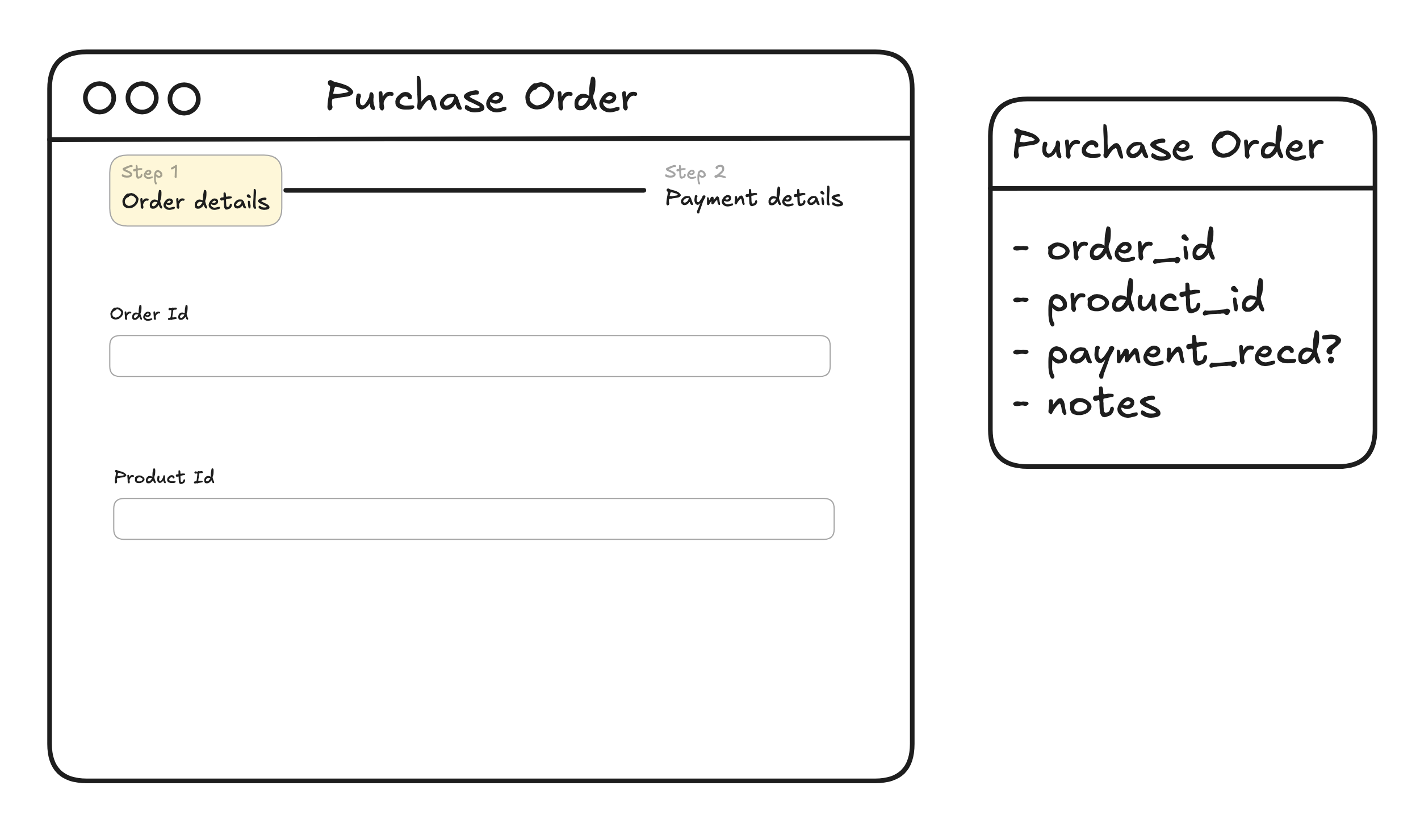

Consider a purchase order. The data schema has order_id, product_id, payment_id, and notes. Four fields, one table. But the UI tells a different story: order details come first, payment details come second. The schema doesn't know that payment should be a separate step. It doesn't know that notes should span the full width, or that customer_id should auto-complete from a search. The UI carries information the data schema never will.

The UI knows about error handling, logical grouping, conditional flows, and user experience across different runtimes like terminal, mobile, and browser. The data schema knows about types and constraints. They're related but not equivalent.

Drag-and-drop builders

Retool, Tooljet, Appsmith, and their clones take a different approach: visual builders where you drag components onto a canvas and wire them to data sources.

The abstraction is wrong. You're still thinking in terms of React components, just dragging them instead of typing them. The output is still runtime-specific. You still need to handle state management, still need to connect to backends, still need to deal with the full complexity of a modern web stack.

These tools reduce typing, not complexity.

The missing layer: UI as schema

What if the UI itself was defined as a schema? Not the data, but the interface.

{

"type": "form",

"title": "Company",

"sections": [

{

"title": "Company Details",

"columns": [

{

"fields": [

{ "name": "company_name", "type": "text", "required": true },

{

"name": "company_type",

"type": "select",

"options": ["Individual", "Company"]

}

]

},

{

"fields": [

{ "name": "registration_number", "type": "text" },

{ "name": "founded_date", "type": "date" }

]

}

]

},

{

"title": "Contact Information",

"condition": { "field": "company_type", "equals": "Company" },

"columns": [

{

"fields": [

{ "name": "contact_email", "type": "email" },

{ "name": "contact_phone", "type": "phone" }

]

}

]

}

],

"submit": { "endpoint": "/api/companies", "method": "POST" }

}

The schema captures intent, not implementation. It says what the UI should do, not how to render it in React or Vue or SwiftUI.

A runtime then interprets this schema. The runtime handles React on web, React Native on mobile, TUI in the terminal. The runtime knows about ShadCN or Material UI or whatever design system you prefer. The runtime deals with state management, form validation, API calls.

The schema is portable. The complexity lives in the runtime.

Why AI would thrive here

AI generating React code is AI solving the wrong problem. It's producing implementation when it should be producing specification.

With a schema-first approach:

- AI defines structure, not syntax. Instead of generating 200 lines of React with hooks and effects and imports, AI produces 50 lines of JSON that declares intent.

- The output works everywhere. Same schema renders on web, mobile, desktop, terminal. No rewriting for each platform.

- The backend connects automatically. If the schema knows about endpoints and models, you close the loop between data and UI.

- Validation happens at the schema level. Is this a valid UI definition? That's answerable. Is this good React code? That's subjective.

- Runtime upgrades happen without touching the schema. Want to swap REST for a sync engine? Change the runtime, not the app definition. Want to upgrade from ShadCN v1 to v2? The schema stays the same.

- Mobile apps can behave like websites. Schemas can be sent over the wire. Update your UI without waiting for app store approval.

The number of moving parts in a typical stack is staggering: backend with its own data schema, API layer (REST or GraphQL or tRPC), sync engine, frontend framework, state management library, component library, form handling library. Each connection is a place for bugs and drift.

A UI schema collapses this. You configure instead of code.

This is what Microsoft's Language Server Protocol did for editors. LSP decoupled what the language provides (completions, diagnostics, go-to-definition) from how the editor renders it. Language teams describe capabilities in a standard protocol; editors interpret that description. The two sides evolve independently.

A UI schema is the same pattern for a subset of applications. Decouple what the app is from how it gets rendered. Describe the application once, let runtimes handle the rest.

Prior art: The infinitely extensible Frappe Framework

Frappe is a full-stack web framework written in Python and JavaScript. It powers ERPNext, one of the most popular open-source ERP systems in the world. The framework is designed for building database-driven applications with minimal code, and its core abstraction is the Doctype.

A Doctype defines:

- The database schema. Field names, types, constraints.

- The UI layout. Field ordering, sections, tabs, column breaks.

- Conditional visibility. Show this field only when that field has a certain value.

- Permissions. Which roles can read, write, create, delete.

- Linked documents. Relationships to other Doctypes.

- Print formats. How to render this as a PDF.

One definition serves data, UI, permissions, and output. The Frappe runtime interprets the Doctype and renders it appropriately: in the Desk interface, on mobile, in print.

// Example Doctype definition

{

"doctype": "Company",

"fields": [

{

"fieldname": "company_name",

"fieldtype": "Data",

"label": "Company Name",

"reqd": 1

},

{

"fieldname": "company_type",

"fieldtype": "Select",

"label": "Type",

"options": "Individual\nCompany"

},

{

"fieldname": "contact_section",

"fieldtype": "Section Break",

"label": "Contact Details",

"depends_on": "eval:doc.company_type=='Company'"

},

{

"fieldname": "contact_email",

"fieldtype": "Data",

"label": "Email",

"options": "Email"

}

],

"permissions": [

{"role": "System Manager", "read": 1, "write": 1},

{"role": "Sales User", "read": 1}

]

}

This is a complete specification. The runtime knows how to render it, validate it, persist it, and control access to it.

What Doctypes get right

Single source of truth

The Doctype is the authoritative definition. There's no drift between database schema, API contract, and UI specification because they're all derived from the same artifact.

Runtime independence

You don't write React. You don't write Python views. You define what you need, and the framework provides it. When Frappe updates its UI, your Doctypes get the update automatically.

Permission integration

UI-level visibility tied to role-based access isn't an afterthought. It's built into the schema. The field definition includes who can see and edit it.

Extensibility

Doctypes support custom scripts for behavior that can't be captured in the schema. But the common cases, around 90% of CRUD operations, need no code.

Another approach: Presto UI

Presto UI takes a different angle. It's not schema-driven in the same way, but it defines UI flows as mathematical equations. The idea is to capture the event-oriented nature of frontends declaratively. Instead of imperative code that mutates state, you describe relationships between inputs and outputs. The runtime figures out the rest.

billPayFlow :: Flow BillPayFailure StatusScreenAction

billPayFlow = do

_ <- UI.splashScreen

operators <- Remote.fetchOperators

operator <- UI.chooseOperator operators

mobileNumber <- UI.askMobileNumber

amount <- UI.askAmount

result <- Remote.payBill mobileNumber amount operator

UI.billPayStatus mobileNumber amount result

Each line is a step. Each step depends on the previous. The flow reads like a specification, not an implementation.

But what about edge cases?

The answer is lifecycle hooks.

No schema covers every case. Sometimes you need to fetch data from an external API before rendering a field. Sometimes you need custom validation that depends on business logic. Sometimes you need to trigger a workflow after a form submits.

Frappe handles this with hooks at both layers:

Python hooks run on the server. They fire at document lifecycle events like before_insert, after_save, on_submit, and before_cancel. You write a function, register it to the event, and the runtime calls it at the right moment.

# hooks.py

doc_events = {

"Sales Order": {

"after_insert": "myapp.sales.notify_warehouse",

"on_submit": "myapp.sales.create_delivery_note"

}

}

JavaScript hooks run on the client. They fire at form lifecycle events like refresh, validate, and before_save. You get access to the form state and can modify behavior, hide fields conditionally, or fetch additional data.

frappe.ui.form.on('Sales Order', {

refresh: function (frm) {

if (frm.doc.status === 'Draft') {

frm.add_custom_button('Send for Approval', () => {

// custom action

});

}

},

customer: function (frm) {

// runs when customer field changes

frappe.call({

method: 'myapp.get_customer_credit',

args: { customer: frm.doc.customer },

callback: (r) => frm.set_value('credit_limit', r.message),

});

},

});

The schema handles the 90%. Hooks handle the 10%. You're still not writing the form. You're injecting behavior into a form the runtime generates.

This pattern lets you integrate schema-first UI into existing systems. Your legacy API? Call it from a hook. Your custom validation logic? Run it in before_save. Your third-party service? Trigger it in after_submit.

The schema is the default. Hooks are the escape hatch.

Should I build this?

This post is a beacon for validation. If you think your project could benefit from a schema-first UI approach, please reach out. Or share this with someone for whom it might be helpful. I want to gauge interest before I commit time to building this.